Are enterprises asking the right questions about data and its storage? This may seem an unusual question – it should not be treated as an abstract issue. If they are not, or if appropriate questions produce unexpected answers, then there may exist distinct possibilities for substantial future savings as well as releasing IT skills for assisting the business.

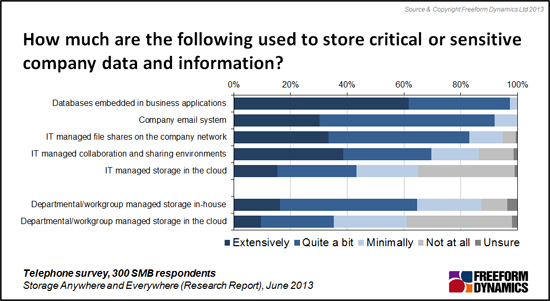

It is a mantra today that data is valuable. The above chart (from a Freeform Dynamics report entitled “Storage Everywhere and Anywhere¨) shows how data found in 300 medium sized enterprises (but likely to apply to larger and smaller ones) continues to expand. To support more and more data most enterprise IT employs specialists to plan, monitor and manage storage. With all the complexities of multi-tiering (primary, secondary, tertiary, tape, online, offline, etc.), plus performance, optimisation and compliance, it is not surprising that many organisations have had to invest in storage technologies to ensure data quality and accessibility. Indeed, most organisations gradually have had to add staffing as their data complexity has increased.

The operative word here is gradual. Remember that even mid-size enterprises can own 100s of terabytes (if not petabytes) of data. Storage has, therefore, become a discipline where the accepted wisdom is often that preserving many generations of data to ensure business continuity is almost more important than what this costs to achieve. This explains in part why enterprises spend so much – on staff as well as storage technologies.

However, think about what happens if you ask questions from a different perspective:

- How often should one store a given piece of data?

- How many times does an enterprise currently store a given piece of data?

- Could there be another approach to storing data more cost efficiently?

These sort of questions are relevant because, all too frequently today’s storage environment embodies an attitude which aims to store core data often, simply to be safe. Undoubtedly this is risk-averse. But is it risk and cost effective?

Practical Context

Some practical context is useful. To illustrate what can happen with today’s practices, make some simple policy assumptions:

- There is 1TB of transactional or core data (some parts may be more critical than others but all data is important)

- A full backup is performed daily, and every day over a seven-day week

- 30 days of these backups are kept

- One copy of each of the most recent past three months is kept as further backup

- A full copy of the current and previous three months of data is kept off-site (for disaster recovery or DR).

Starting with that 1TB of data (and remembering that that this is only an example), this means there is:

- 7TB by the end of the week (1TB per day)

- 30TB by the end of the month (30 days/month)

- 120TB after adding the three copies of the previous three months

- 240TB when the DR site is included

- A given piece of data is stored some 240 times the original 1TB – which gives a Data Stored Factor (DSF) of 240.

You may well argue that such a DSF (of 240) is excessively high. Let us change the assumptions. If only 20% of data changes or is added each day (indeed this is why some organisations still use full plus differential backups, to minimise recovery times), this would reduce the DSF as follows:

- The daily increase would be ’only’ 0.2TB/day, to add to the existing 1TB

- The weekly addition then becomes 1.4TB

- The monthly increase is then 6TB after 30 days

- After adding the three generations of monthly backup this amounts to 24TB

- The ongoing total is 48TB once the data copy for DR is included, or a DSF of 48.

A DSF of 48 is undoubtedly much more efficient than the previous ’crude’ DSF of 240, but it is horrifying enough. Would you buy a car if you knew you needed to purchase of another 47 (or even another 2-3) cars in order to be economically certain of being able to travel to work?

Furthermore, remember that the DSF examples calculated above, of 48 and 240, are deliberately simple and only about core to make the pint. They do not reflect or include:

- Disk usage/performance efficiency considerations – (though this will only apply to the primary disks it can be as low as 20%-25%)

- Snapshots – (which may add 10-20% of storage per day depending on the operational efficiency requirements though it is also true that snapshots can reduce the number of backup copies kept)

- Compliance considerations

- Allowances for growth or for the many new types of data arriving; for example Twitter messages may only be 140 characters each but there may be many, many tweets relevant to your enterprise’s social image; similarly, distributed computing, voice, mobile devices and other media are becoming ever more relevant and needing storage space.

The key issue that DSF should raise is about the cost effectiveness of existing storage implementations, including storage technologies, infrastructure and staff. In that context:

- Does your organisation know how many times it is storing any given piece of data?

- Has this ever been considered?

- Does anybody know what would be regarded as a cost efficient / risk effective DSF?

- Are different DSFs applicable to different categories of data?

How many times should an enterprise store its data?

Storage administrators do not set out to ’over-store’, though this approach is no doubt backed up by compliance officers arguing that you cannot store a piece of data often enough. What has really occurred is that modern storage technologies have improved hugely in reliability but past storage practices, formulated when storage was not so reliable, have not kept pace.

Reflect that even mandated custodians — like the Library of Congress or the British Library — which try to keep everything seek not to keep excessive duplicates. For the sake of argument, now consider some arbitrary DSF efficiency possibilities:

- 1 original is clearly is insufficient in a digital environment

- 2 copies are much better (which is why DR exists)

- 4 copies (2 at the source and 2 at DR) is better still

- 8 copies (4 at the source and 4 at DR) is safer than 4 — though some might ask what do the extra 4 copies deliver?

- above (say) 8 copies, storage costs increase with little obvious cost-effectiveness gain

- 48 copies seems simply excessive while 240 seems unimaginably ridiculous, and wasteful

In this context, however, some data will be different. A real challenge is separating changed data from unchanged data and protecting both ways which facilitate suitable recovery time objectives to be met. Even after considering this the last two (on the list above) reflect what, as described earlier, can happen in many enterprises which have not updated their storage practices to fit the much improved reliability of storage technologies or to utilise new data protection solutions which can minimise the total data stored at each iteration of protection.

In this context it is improbable that only one DSF will apply to all data or even to all organisations. Different organisations will need different DSFs and for different types of data. A bank, for example, may well have a need for a higher DSF for core data than (say) a mid-size manufacturing or retailing organisation. The potential technology and staff savings will likely be significant. This really is a case of one size does not fit all.

If, however, you start by defining what a cost effective target DSF might be, this can inform a cost effective data storage strategy and how you should implement this.

CLICK HERE TO VIEW ORIGINAL PUBLISHED ON

Content Contributors: Charles Brett

Through our research and insights, we help bridge the gap between technology buyers and sellers.

Have You Read This?

From Barcode Scanning to Smart Data Capture

Beyond the Barcode: Smart Data Capture

The Evolving Role of Converged Infrastructure in Modern IT

Evaluating the Potential of Hyper-Converged Storage

Kubernetes as an enterprise multi-cloud enabler

A CX perspective on the Contact Centre

Automation of SAP Master Data Management

Tackling the software skills crunch