How we should be protecting our PCs

Security threats have existed for almost as long as computers have been around.

Few interactive systems can claim to be immune – even venerable systems like the IBM mainframe, UNIVAC and VAX have had their share of malware. Then, the PC brought computing to the masses, but also brought a new environment for malware to bloom.

The ‘sneaker net’ at first kept the rate of spread at a relatively low level. However, once networking, and especially the Internet, became pervasive, threats began to spread rapaciously.

The initial generations of malware focused on publicity or damage, with the main financial costs coming from lost productivity and the subsequent clean-up and potential for damage to the brand and reputation of the company. The rise of online shopping and commerce, and social identities have created a new target for malware creators that is financially motivated – bringing in organised crime on a huge scale. When we look at how virtualisation is changing PC use, and how quickly threats evolve, how should we be looking to secure not just our PCs, but also the users that most often really are ‘the weakest link’?

Starting with those end-users, education and policy remains a continued weak point in IT, and especially PC, security. From writing down logins and passwords, sharing logins, emailing or copying sensitive information – not to mention clicking on attachments to emails promising a nice eyeful or that somebody loves them – the habits of PC users often have the biggest impact on the effectiveness of any security solution.

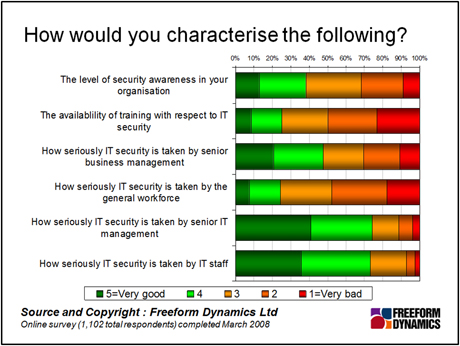

Unfortunately, the attitude of end-users to security is often laissez-faire, and this comes from the culture of the company and its attitude to security and the investment put into training users to be security conscious. We can see from the figures below that for many companies, raising the level of security is far from top of mind. To close the loop and improve security overall, there is almost no better place to start from than getting management to realise the implications of security breaches, and to develop a security policy that can be communicated to the workforce.

It is vital that users are educated to be aware of and understand the security implications of their actions. Few people would sticky-tape their keys to their car after all, even a company car, as the consequences would be pretty severe. Yet this is effectively what they do when providing access details for critical business systems with little or no repercussion.

It is important to realise that traditional methods of protection are not going to suddenly become irrelevant. Anti-malware software will continue to be necessary to cover much of the mature threat landscape. New techniques, such as content filtering, data protection and web protection may enhance and augment these systems, but they are extending and not replacing the functionality.

With the security threat moving from damage and notoriety to identity and money, the perpetrators are looking at ever more covert ways to operate, and are moving off the PC and onto the web. This brings a huge security space to cover and is much broader than trying to protect individual PCs. This will bring about a change in security protection where network or Internet-based security services work alongside those running on the PC. This is starting to become well established as a concept, especially for malware such as anti-spam, and is starting to gain relevance for web content and financial interactions.

We are also likely to see a change in how vendors architect security solutions, and this will affect how they are deployed on PCs. This change is being driven by virtualisation, which is throwing a spanner in the security works. With multiple Operating Systems (OSs) running, just where and at what level should security software really be functioning? Running full-blown security solutions on all virtual machines is inefficient, a resource hog, and requires management to avoid conflicts and redundant processing.

For type 2 hypervisors, where guest OSs run on top of a host OS, few products – if any – are capable of securing guest OSs from the host OS. And where the guest runs directly on a type 1 hypervisor, products have yet to emerge that can act as a sentinel to provide centralised, low-level security.

The ideal solution will be to have a thin security layer, or ‘client’ for each virtual machine that then communicates with a ‘server’ running on the host OS or in conjunction with the hypervisor. The security scanning and processing can be co-ordinated, and common elements shared for maximum efficiency. The trick will be getting up and running with these emerging solutions in parallel with the move to deploying virtualisation on PCs. Leaving it too late will very likely result in a wholly unsatisfactory user experience, and an unmanageable security soup.

Content Contributors: Andrew Buss

Through our research and insights, we help bridge the gap between technology buyers and sellers.

Have You Read This?

Generative AI Checkpoint

From Barcode Scanning to Smart Data Capture

Beyond the Barcode: Smart Data Capture

The Evolving Role of Converged Infrastructure in Modern IT

Evaluating the Potential of Hyper-Converged Storage

Kubernetes as an enterprise multi-cloud enabler

A CX perspective on the Contact Centre

Automation of SAP Master Data Management